Module 2: Connections to the Land and Indigenous Worldviews

Module 2: Connections to the Land and Indigenous Worldviews

Journal Entry: Power of Indigenous Kinship

Kinship and Community in the Classroom

Reading The Power of Indigenous Kinship by Tanya Talaga and exploring the Kinship Rock in Walking Together deepened my understanding of how Indigenous worldviews are rooted in relationships—not just with people, but with the land, animals, ancestors, and future generations. Kinship is not limited to blood ties; it is a way of being in the world that emphasizes responsibility, reciprocity, and respect.

In my classroom, I strive to build community by creating a space where every student feels seen, valued, and connected. I use strategies like daily check-ins, collaborative group work, and storytelling circles to foster trust and belonging. However, the kinship model invites me to go further—to see my students not just as learners, but as relatives in a shared journey of growth and care.

Moving forward, I will incorporate kinship philosophies by:

- Framing classroom agreements as relational commitments—not just rules, but ways we care for one another.

- Integrating land-based learning where possible, encouraging students to build relationships with the natural world around them.

- Honouring multiple ways of knowing, including emotional, spiritual, and experiential knowledge.

- Using circle pedagogy to emphasize equality, listening, and shared responsibility.

This shift is not just about classroom management—it’s about transforming the classroom into a living community where learning is rooted in connection, care, and collective responsibility.

Traditional Wisdom and Ecological Knowledge: The Integral Role of Cedar in Coast Salish Culture

CEDAR USES

Cedar Bark is used for weaving baskets, mats, and clothing

Cedar Wood is used in constructing longhouses, canoes, and totem poles

Medicinal Uses: Cedar Tea is brewed for immune support and treating colds

Steam Inhalation relieves respiratory issues like congestion

Cedar Baths purify and sooth skin conditions and muscles

Salves and Poultices are made for cuts and skin irritations due to antiseptic properties in cedar

Aromatherapy calms and enhances mental clarity

Ceremonial Uses: Cedar is incorporated into cultural rituals and ceremonies as an essential element

SPECIFICALLY:

Yellow Cedar bark is softer and more pliable, used mainly for clothing and fibrous materials.

Western Red Cedar is lightweight, rot-resistant, and used for architecture and transportation (house poles, canoes).

CEDAR LOCATIONS

Yellow Cedar

Size: 20 to 40 metres tall.

Habitat: Subalpine elevations in damp coastal forests from Vancouver Island to Alaska; rarely inland.

Western Red Cedar

Size: Up to 70 metres tall, can live up to 1,000 years.

Habitat: Coastal regions and moist slopes and valleys of the Interior.

INDIGENOUS NAME

The Hul’qum’inum’ name for cedar wood, and sometimes the tree, is xpeyʔ. The tree itself is also called xpeyʔ-əłp, adding the suffix -əłp, meaning “plant or tree”. Cedar is revered and also known and referred to as the “Tree of Life”, Grandmother, and Long-Life Maker.

HARVEST AND PRESERVATION METHODS

Almost every part of a cedar tree is used, including the roots, bark, wood, and withes (smaller, pliable branches).

Harvesting Practices

Respectful Harvesting: Before cutting down a tree, woodcutters say a prayer and express gratitude to the tree’s spirit.

Men's Role: Traditionally, men cut down trees using chisels and red-hot stones to weaken the wood. They used tools like stone adzes and bone drills.

Women's Role: Women typically harvested the bark, choosing straight, young trees and de-barking only portions to ensure the tree's survival.

Preservation Methods

Sustainable Harvesting: Only portions of the tree are de-barked, leaving distinctive scar marks.

Culturally Modified Trees (CMTs): These trees, with their scar marks, are found in old-growth forests and are considered important heritage sites.

Legal Protection: In B.C., sites with CMTs created before 1846 are protected by law.

Modern Practices: Indigenous peoples continue to create new CMTs, using sustainable methods passed down from their ancestors.

OTHER FACTS AND DESIGN FEATURES

- Cedar trees are believed to have their own life and spirit. Coast Salish and Tlingit shamans often had cedar “spirit assistants” or “guard figures” to protect them

- Improper harvesting could curse the harvester, and pregnant women were advised not to braid baskets to avoid complications during childbirth

- Cedar symbolizes strength and revitalization, reflecting its role in ensuring the survival of people for thousands of years

- Longhouses, central to village life, were constructed with cedar poles and beams. Carved house frontal poles depicted family crests and lineage

- Coast Salish and Nuu-chah-nulth peoples have creation stories that explain the origins of cedar trees, highlighting their cultural and spiritual significance

- Indigenous stewardship practices, such as selective harvesting and reforestation, ensure the sustainability of cedar trees. Efforts to integrate traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) into modern conservation practices highlight the importance of Indigenous stewardship to maintain ecological balance and cultural heritage

REFLECTION

Researching cedar has increased my appreciation for its multifaceted roles in Coast Salish culture. Beyond itspractical uses, such as construction and crafting, cedarembodies a profound connection with the environment andsymbolizes life, sustainability, and well-being. Understandingits medicinal applications, like cedar tea for immune supportand steam inhalation for respiratory relief, highlights theholistic approach to health that is deeply ingrained inIndigenous practices. This comprehensive view of cedar’ssignificance underscores the valuable lessons modernpractices can learn from traditional knowledge andemphasizes the importance of respecting and integratingIndigenous wisdom in contemporary sustainability andwellness strategies. One lesson I remember learning is aboutthe value of TEK when tree planting after deforestation. AFirst Nations biologist was planting saplings according togovernment direction which overlooked the needs of theEarth and cedar plants. When the biologist returned to thisforest, all the young saplings were dead. These saplings were planted in the wrong season and in unsuitable locations. This experience underscores the critical role of TEK in ensuring the survival and health of reforested areas.

REFERENCES

What Is Your Connection to Land?

Who They Are?

· Murray Sinclair was born in 1951 near Selkirk Manitoba on the former St. Peter’s Reserve. He died on November 4, 2024, in Winnipeg, Manitoba.

· Murray Sinclair was a member of Peguis First Nation. He and his three siblings were raised by his grandparents, and at an early age he was a promising and dedicated student. After postponing his university degree to care for his grandmother, he eventually became interested and passionate about law.

o Graduated from University of Manitoba’s Faculty of Law (1979)

o First Indigenous judge in Manitoba (1988)

o First Indigenous judge appointed to the Court of the King’s Bench (then Queen’s bench) (2001)

What Their Work Is:

· Judicial Career:

o Co-commissioner, Manitoba’s Aboriginal Justice Inquiry (1988-1991)

o Recommendations led to Gladue principles (1996)

· Truth and Reconciliation Commission:

o Chief Commissioner (2009-2015)

o Documented residential school survivors' experiences

o TRC’s final report with 94 Calls to Action

· Beyond:

o Senator (2016-2021)

o Chancellor, Queen’s University (2021-2024)

o Author, Who We Are: Four Questions for a Life and a Nation (2024)

What Makes Their Work Significant

· Impact on Indigenous Governance:

o TRC: Shed light on the legacy of residential schools

o 94 Calls to Action: Blueprint for reconciliation

o Aboriginal Justice Inquiry: Addressed systemic discrimination in justice system

· Advocacy for Indigenous Rights:

o Promoted understanding and compassion between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples

o Focused on justice and dignity for Indigenous communities

Why I chose the late Honourable Murray Sinclair

· I chose the late Honourable Murray Sinclair as an Indigenous Leader because he exemplifies an inspirational figure with significant influence across all levels of government in Canada.

· His words inspire both Indigenous and non-Indigenous people to engage in the essential work of achieving reconciliation.

· As a teacher of a B.C. First Peoples course, I find that my students can connect with Murray Sinclair’s story and his tireless advocacy for Indigenous dignity and rights. His work on the Truth and Reconciliation Commission is only one example of his lifetime of achievements.

Other Images or Information:

· I shared the audiobook Who We Are with my class and listening to Murray Sinclair’s words from his voice really facilitated my students’ connection to his story and his message.

· He advocated about the critical importance of everyone in our nation working together to achieve reconciliation.

· His awards are numerous and include Companion of the Order of Canada, Order of Manitoba, King’s Counsel designation (Queen’s Counsel then), and 30+ honorary doctorates. On a personal note, he was the chancellor of Queen’s University while my son was enrolled. Unfortunately, the Honourable Murray Sinclair did not perform my son’s convocation in 2024.

REFERENCES

- Canadian Heritage. (n.d.). In memory of the Honourable Murray Sinclair. https://www.canada.ca/en/canadian-heritage/commemoration/murray-sinclair.html

- Harvard Project on Indigenous Governance and Development. (n.d.). Project on Indigenous Governance and Development. https://indigenousgov.hks.harvard.edu/

- Native Governance Center. (n.d.). Indigenous Leaders in Governance. https://nativegov.org/programs/tribal-governance-support/indigenous-leaders-in-governance/

- Sinclair, M., Sinclair, S., & Sinclair, N. (2024). Who We Are: Four Questions For a Life and a Nation. Penguin Random House.

- The Canadian Encyclopedia. (n.d.). Murray Sinclair. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/murray-Sinclair

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (n.d.). TRC Reports. https://nctr.ca/records/reports/

Researching Climate Activism and Environmental Leadership Initiatives

Caribou Habitat and Restoration

The Cheslatta Carrier Nation located on the bank of Francois Lake have undertaken an initiative with B.C. Ministries to restore the Tweedsmuir-Entiako caribou migration routes that have been heavily impacted by forest harvesting and the roads they require.

This initiative incorporates:

Ecological restoration - site preparation and planting of conifer trees to rebuild habitat

Functional restoration - creating natural barriers, like berms, to reduce line of sight to roads and limit human access

Lakeshore restoration - the Cheslatta Carrier Nation has also undertaken studies that show clearing debris from lakeshores also allows young caribou to access fresh water easily.

This initiative improves the biodiversity of the land, restores native populations, and improves food security for all Indigenous populations along the caribou migration routes. By restoring forests and native plants, the project helps the land recover from environmental damage and become more resilient to the effects of climate change, such as habitat loss and extreme weather. It also supports the return of species that are important to both the ecosystem and Indigenous cultural practices.

In the classroom, I could have students explore how Indigenous communities lead climate action through land-based knowledge and stewardship. We could further explore how Traditional Ecological Knowledge supports a healthy ecosystem and climate resilience. Finally we could explore the goals of Truth and Reconciliation in the joint initiatives that support Indigenous leadership in environmental sustainability. https://hctf.ca/category/caribouprojects/ https://www.cheslatta.com/environmental:stewardship

https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/1KGkkDnGEBE-sMbXGYYK5-kyZmNFdNjLFO6Kc3vwxMII/edit?usp=sharing

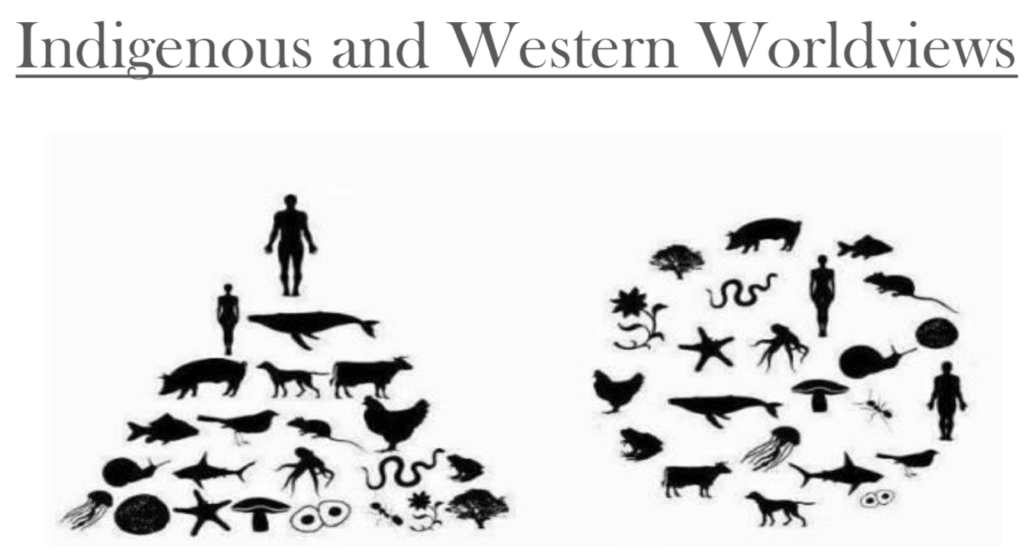

Comparing Worldviews

I think the Indigenous worldview—rooted in wisdom, stewardship, protection, relationship, and kinship with land, air, water, and more-than-human kin—can deeply enrich the classroom context. From our discussions, I am already planning to work with our Indigenous Coordinator to take my students out on the land to learn about Indigenous plants and TEK. I am learning that Indigenous knowledge systems are not just content to be taught, but ways of being and relating that can shape how we teach, learn, and connect. This is taking me time to put into practice but with so many fabulous peers in this class, I am adding to my practice as I learn.

In the classroom, this might look like:

- Land-based learning: Taking students outside to learn from the land and learn about Indigenous plants, their uses, and their names.

- Relational pedagogy: Encouraging students to see themselves in relationship with their peers, the environment, and their community.

- Storytelling: Using oral traditions to transmit knowledge and values.

- Respect for more-than-human kin: Teaching students to see animals, plants, and ecosystems as relatives, not resources.

“Two-Eyed Seeing” (Etuaptmumk), as described by Rebecca Thomas, invites people to respect and honour Indigenous knowledge. Also we are asked to understand Indigenous "peoplehood" as more than just an individual, rather as one and their connections to others, community and identity. I found Thomas's example of how language shapes our worldview very impactful and reminds me to create space in classroom and my own learning for understanding the value of both Traditional and Scientific ways of knowing being valid.

In practice, this could mean:

- Designing units that explore both scientific and Indigenous understandings of ecosystems.

- Encouraging critical thinking about how knowledge is created and whose voices are centered.

Questions:

- How can schools build sustained, respectful partnerships with Indigenous communities?

- What does authentic land-based education look like in urban or resource-limited settings?

- How can I, as a non-Indigenous educator, teach BCFP 12 with authenticity, respect, and integrity—ensuring that I am uplifting Indigenous knowledge and voices rather than misrepresenting them?

References

Lees, A., & Bang, M. (2023). Indigenous Pedagogies: Land, Water, and Kinship. Occasional Paper Series, 2023(49). https://doi.org/10.58295/2375-3668.1500

TEDx Talks. (2016). Etuaptmumk: Two-Eyed Seeing | Rebecca Thomas | TEDxNSCCWaterfront. In YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bA9EwcFbVfg

wc nativenews. (2014). The Indigenous world view vs. Western world view. In YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hsh-NcZyuiI

Theme | Indigenous Worldview | Western Worldview |

Kinship | All beings are kin; relationships are sacred and reciprocal | Kinship is human-centered; nature is often objectified or commodified |

Sustainability | Based on balance, respect, and long-term relational accountability; stewardship since time immemorial | Often driven by consumption, growth, and short-term gain. No consideration for impact on long-term sustainability of consumerism economy |

Economies | Gift economies, sharing, and collective well-being; based on abundance: we see this in the Potlach ceremony | Market economies based on scarcity, competition, and accumulation. Resources are seen as limited and war with each other to possess them. |

Nature Practices | Nature is alive and sacred; practices are ceremonial and relational | Nature is a resource to be controlled or extracted |

Competition | Emphasis on cooperation, balance, and mutual support | Competition is seen as essential to progress and innovation |

Knowledge Systems | Oral, experiential, and intergenerational; rooted in place and story; passed down from generation to generation | Empirical, written, and often abstracted from place or community; superiority of written, proven knowledge and facts |

Education | Holistic, land-based, and community-embedded; supports identity and belonging | Formal, standardized, and often disconnected from lived experience |

Land as Pedagogy

This was a very information packed article but it had so many wonderful pieces of wisdom

3 Big Ideas

Land as Pedagogy: True Indigenous education is rooted in the land, not in institutions. The land is both the context and the teacher, and learning is relational, spiritual, and embodied. This was my biggest takeaway and I am still learning how I can facilitate this happens with my students.

Nishnaabeg Intelligence as Resurgence: Resurgence is not about inclusion in colonial systems but about rebuilding Indigenous knowledge systems on their own terms, through practice, resistance, and community. WOW! I have been exploring the terms Resilience and Resistance, but I really resonate with the word Resurgence and how it is explored in this article.

Relational and Consensual Learning: Knowledge is generated through reciprocal, consensual relationships with all beings—human and non-human. Consent, love, and respect are foundational to learning. This is a one that I will work hard to support my own learning, coming back to the power of language from Rebecca Thomas. Changing my language will help change my worldview.

2 Key Insights

The academic education system cannot contain Nishnaabeg intelligence: Institutions often fail to recognize the depth, ethics, and legitimacy of Indigenous knowledge systems. Real resurgence happens on the land, not in lecture halls. This is why Indigenous students in many western worldview schools are not able to connect with the learning (way and content)

Children are central to resurgence: Raising a generation of land-based, community-rooted thinkers is essential. Education should nurture joy, consent, and cultural identity—not just prepare students for capitalist careers. YES! Exactly why the Indian act started with the children, starting a resurgence begins with the young, again coming back to Rebecca, Indigenous populations are the fastest growing demographics in Canada!

1 Question

Whose knowledge systems are centered in my work—and whose are marginalized or missing?

Simpson, L. (2014). Land as pedagogy: Nishnaabeg intelligence and rebellious transformation 1. http://whereareyouquetzalcoatl.com/mesofigurineproject/EthnicAndIndigenousStudiesArticles/Simpson2014.pdf

Module 2 Reflection: Connections to the Land and Indigenous Worldviews

1. The Power of Indigenous Kinship by Tanya Talaga

Summary: Talaga’s article emphasized that kinship in Indigenous worldviews extends beyond family to include land, ancestors, and future generations. Kinship is about responsibility, care, and interconnectedness.

Why I Chose This: It helped me reframe how I think about classroom community—not just as a group of individuals, but as a network of relationships.

Classroom Application: I will use circle discussions and co-created classroom agreements to foster a sense of shared responsibility and relational care among students.

2. Knowledge Keepers: Medicine Walk and Cedar Harvest (MOA Documentary Series)

Summary: These videos showed how Indigenous knowledge is passed down through land-based practices and relationships with plants and ecosystems. Cedar, for example, is not just a resource—it is a relative, harvested with ceremony and respect.

Why I Chose This: It deepened my understanding of Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) and the importance of protocol and reciprocity in learning from the land.

Classroom Application: I will incorporate local plant studies into science and social studies, emphasizing respectful harvesting, storytelling, and Indigenous perspectives on sustainability.

3. Two-Eyed Seeing (Rebecca Thomas TEDx + California Academy of Sciences video)

Summary: Two-Eyed Seeing is the practice of viewing the world through both Indigenous and Western knowledge systems. It values both ways of knowing without trying to merge or erase either.

Why I Chose This: It offers a powerful framework for integrating Indigenous perspectives into curriculum without appropriating or diluting them.

Classroom Application: I will use Two-Eyed Seeing to guide interdisciplinary projects—such as combining Indigenous ecological knowledge with Western science in environmental studies.

4. Land as Pedagogy by Leanne Betasamosake Simpson

Summary: Simpson argues that land is not just a backdrop for learning—it is a teacher. Learning from the land requires presence, humility, and a willingness to unlearn colonial assumptions.

Why I Chose This: It challenged me to think beyond classroom walls and see land-based learning as essential to education.

Classroom Application: I will plan regular outdoor learning experiences where students observe, reflect, and build relationships with the land, guided by the First Peoples Principles of Learning.

Module 2 Culminating Task: Creating a Presentation

Comments

Post a Comment